La primera pintura conocida sobre la Isla de Pascua, de William Hodges (1775)

Crear en Salamanca tiene la satisfacción de publicar el pórtico que el poeta Alfredo Pérez Alencart escribiera para el poemario“Toma de razón / He haka topa mana’u / Rights taken” (Mago Editores, Santiago de Chile, julio 2017, pp. 86), obra escrita por los poetas y jueces chilenos Víctor Ilich y Roberto Conteras Olivares, con traducción al inglés (Gretchen Abernathy) y al rapanui (Sabrina Atamu Atan). El mismo fue presentado el 18 de agosto en el Centro Cultural Tongariki, dependiente de la Corporación Municipal de la Cultura y las Artes de la Isla de Pascua, situado en la población de Hanga Roa.

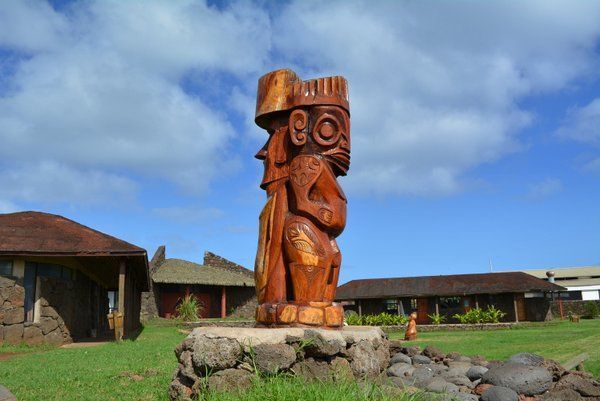

El Centro Cultural Tongariki, en hanga Roa, Isla de Pascua

ALEGATO LÍRICO POR RAPA NUI

La isla de Pascua es un pedazo de suelo chileno distante a más de 3.600 kilómetros del territorio continental. Si ya Neruda atisbaba, allá por 1971, la insostenible ecuación entre nativos y visitantes, imagínese -usted lector- el panorama actual, con noventa y cinco mil turistas al año paseando entre moáis y consumiendo a la manera occidental, sin contar a los seis mil quinientos habitantes: Más de siete toneladas diarias de residuos que, en su mayor parte, no se reciclan. Eso sin incluir la contaminación de sus mantos acuíferos debido a los pozos sépticos y a la casi nula red de cloacas…

Lo que otrora parecía un idílico refugio insular, el punto terrestre más alejado de cualquier otro espacio habitado del planeta, referencia siempre presente en el imaginario de muchos que gustarían alejarse de tantos ruidos y ajetreos de las grandes urbes, hoy está en serio peligro medioambiental.

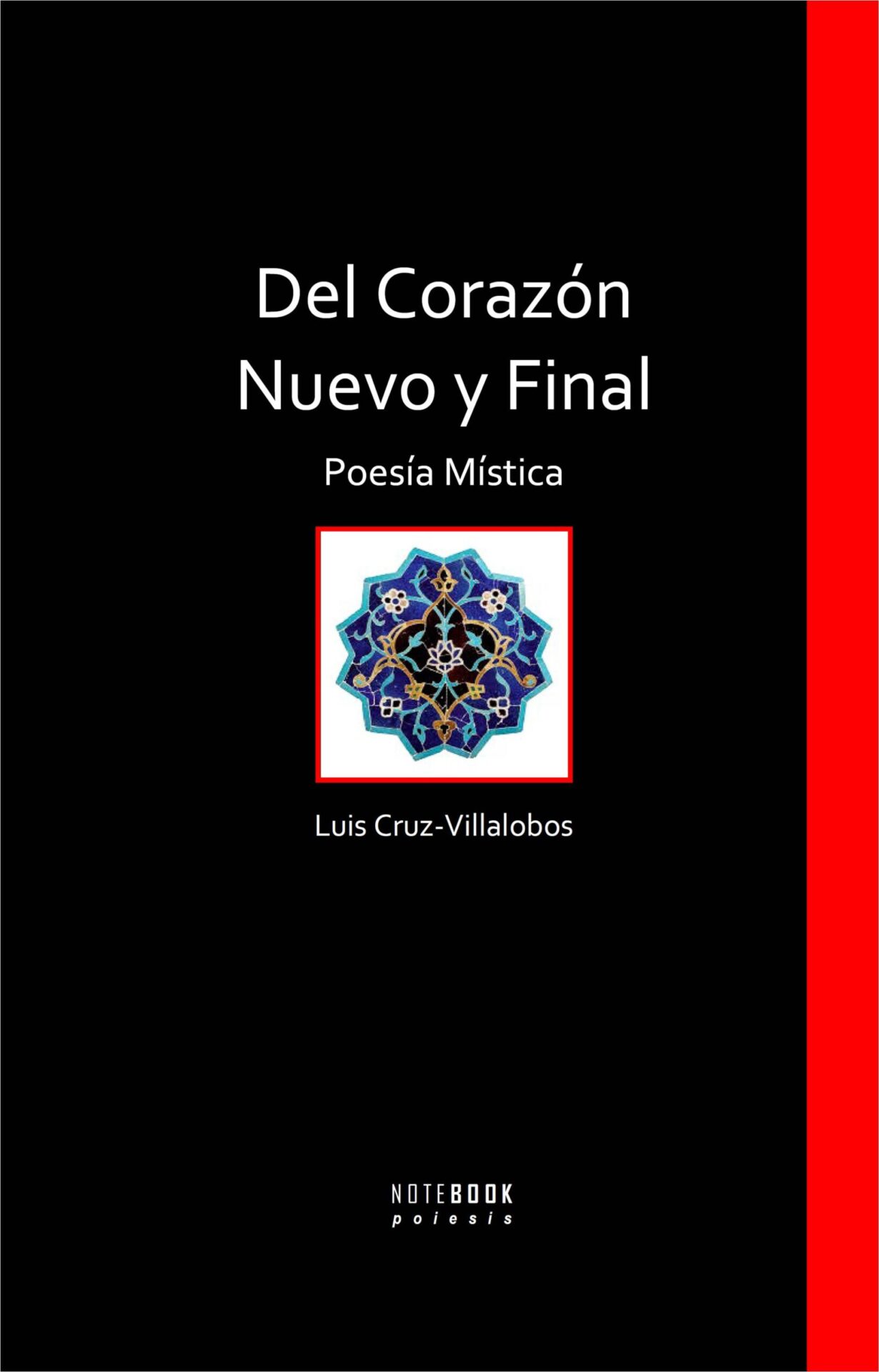

Portada de Toma de Razón

I.

¿Qué creen que es la Poesía?, ¿sólo imágenes batidas al azar, sólo visiones volátiles, sólo belleza destilada para generar innúmeros oh, ah, oh…? Algo de eso resulta válido, porque en el hombre todavía no ha desaparecido la admiración ante lo maravilloso que también es cotidiano.

Pero cuidado en estimar que los poetas no deben tomar conciencia sobre lo que atañe a la realidad más inmediata, sean atentados contra la naturaleza que habita, sean injusticias contra la dignidad de sus congéneres. Alta lírica se ha escrito en torno a ello desde nuestros magnos griegos y latinos. Y sin caer en el panfleto.

Así juzgo la primera parte del poemario Toma de Razón, escrito por Víctor Ilich, Juez Titular del Juzgado de Garantía de San Vicente de Tagua Tagua. Son 12 textos breves, intensos y reveladores, escritos pensando en Rapa Nui, en esa Isla de Pascua de hoy, aquejada por la problemática apuntada al principio.

Atendamos a lo que Ilich anota en su canto VII:

Nunca he hecho un moái,

ni mis antepasados los tallaron,

desde la cantera de mis versos

solo he desgarrado un NO HAY.

No hay más espacio,

solo son 163 kilómetros cuadrados.

No hay más espacio,

ni para un alfiler olvidado.

No hay más espacio en Hanga Roa

para los mercenarios del cambio climático.

No hay más espacio, te digo,

solo el corazón se ensancha

cuando la raíz toca el borde de otra alma.

El sistema jurídico chileno tiene, en la Toma de razón, un mecanismo de control sobre la legalidad de ciertas normas. Es obligatorio y corresponde a la Contraloría General. Aquí, el poeta-juez se torna contralor de las necesidades de los pascuenses, sin importarle que algunos cuestionen el porqué de su interés. Por eso, en su canto XI, deja bien diáfana su intención:

¿Y tú qué sabes de la Isla de Pascua?

Que está sufriendo y eso basta.

Hay que construir un puente

hacia las necesidades del alma.

Me conmueve en grado sumo leer esta toma de conciencia en los doce cantos de Víctor Ilich, pues sé que sus versos llegarán profundamente a los habitantes de Rapa Nui, una tierra que tiene algunos poetas excelentes, como el también abogado Mata-Uiroa Manuel Atan, quien, viendo la bandera, clama: “Todos los días/ despierto/ tú eres mi saludo// Con mi viento/ tú respiras/ encima de mi tierra/ tú flameas// Todos los días/ estoy sentado/ te veo a ti/ me clavas el corazón// Son felices los descendientes de Hotu/ si caminan en Hangaroa/ y tú no estás en el mástil// Oye pabellón de guerra/ de los ancestros extranjeros,/ da un paso/ déjame respirar…”.

Ahora, en su isla, este sabrá dar un grande abrazo a Víctor Ilich, quien escribió sus cantos pascuenses en medio de los pavorosos incendios que asolaban la parte continental de Chile: “Con ascuas de fuego sobre mi cabeza/ y un fuego inmenso en mis huesos/ que aun queriendo apagar no puedo”.

La Poesía es refugio de la verdad, tan escasa en nuestros tiempos.

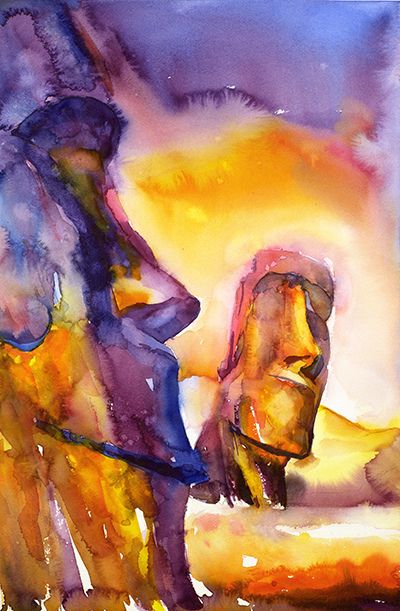

Obra de Ryan Fox

III.

También la Poesía tiene su cetro en el Amor y ha sabido nutrir a la Leyenda. Más próximo al Neruda de La rosa separada, pero marcando su propia impronta, tenemos a Roberto Contreras Olivares, Ministro de la Corte de Apelaciones de San Miguel, autor de la segunda parte de Toma de Razón. Se trata de un poeta cuajado, con varios poemarios precedentes, tal como su compañero Ilich. Su ofrenda se decanta hacia la historia genética y mítica. Para ello se sirve de un baile ¿imaginario? con la reina del Tapati, como buscando un “mutuo destino” de las sangres.

Apreciemos buena parte de su canto XII:

Esta noche, estoy cierto, esta noche

recordaré su nombre

que llevo prendido en mí

cuando esa otra noche

tomé sus manos

en la isla

y bailamos

con las olas

que golpeaban los riscos,

cuando las aves

graznaban

y el anciano pájaro manutara

ponía

el único huevo

tallado de signos

ancestrales…

IV.

Hacia la comunión entre todos los chilenos alienta este poemario, pero sin dejar de recordar a quienes habitaron originalmente la isla. Tal como lo hace otro destacado poeta y antropólogo pascuense, Clemente Hereveri Tao, fallecido en 2007, en su poema “Ancestro navegante”, dice así: “Oh lluvia del infinito/ cae por favor/ para que nuestras bocas no se/ sequen/ con la salinidad del océano/ mientras navegamos/ al ombligo del mundo/ en la mitad del mar”.

Y ya que Toma de Razón está escrito pensando en los habitantes de Rapa Nui, atendamos el texto de Haraveri en su lengua natal:

E te ua o te rani e

A hoa mai koe

O kavaro to matou haha

I nei, i te vaena o te moana

E hura nei

Ki te pito o te henua

I te vaena o te moana

V.

Allí, por la Polinesia chilena, se oirán los versos de Contreras, supongamos que por las alturas del volcán Ranu Raraku; supongamos que recitados por un familiar de Clemente:

Allí, de pie,

mirando en la isla,

somos semillas

para otros astros

de constelaciones emergentes,

perdidos aún

y ciegos.

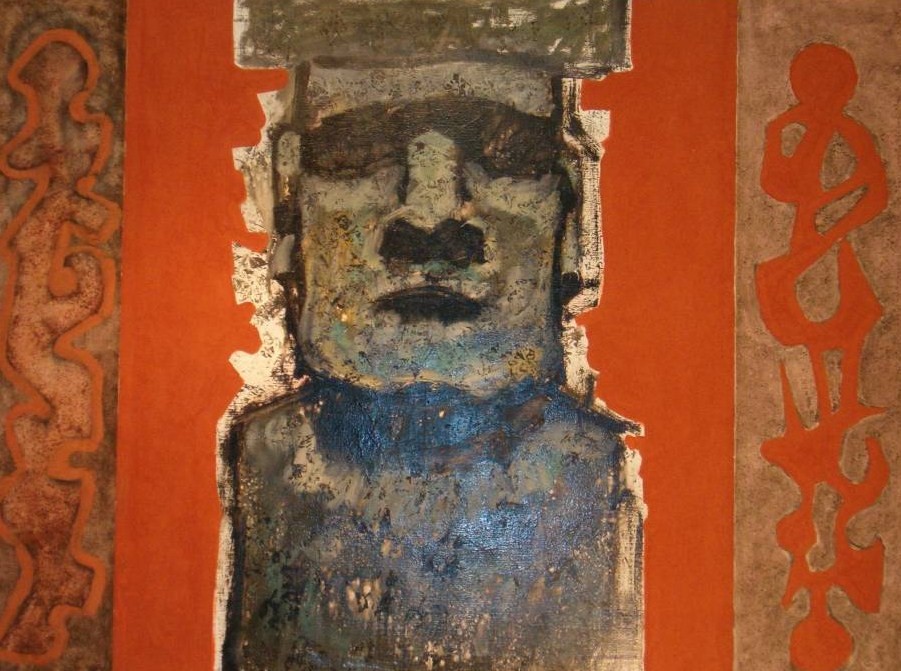

Moais, de Ana Lamelas

VI.

¿Poesía ecológica o poesía amorosa y telúrica? Simplemente Poesía, a secas, es lo que ofrecen, en perfecto connubio lírico, Víctor Ilich y Roberto Contreras Olivares.

Así es como se va construyendo un irrenunciable Derecho a la Poesía.

Así es como ni unos ni otros se sentirán forasteros.

Así es como perdura el canto de siempre.

Ena é, tangi nei.

Ena é. Tangi- tangi-nei

(Este es el canto…

Este es el canto que hace llorar…).

Abril y en Tejares (2017)

Alfredo Pérez Alencart

Universidad de Salamanca

Víctor Ilich y Roberto Contreras Olivares

LYRICAL PLEA FOR RAPA NUI

A aster Island is a speck of Chilean soil over 3,600 kilometers off the coast of South America. If Neruda could foresee back in 1971 the unsustainable equation between natives and visitors, imagine, dear reader, what it’s like today, with 95,000 tourists per year traipsing about the moai and consuming the island at a Western pace, in addition to the 6,000 inhabitants: nearly seven tons of waste per day that, for the most part, go unrecycled. Not to mention the contamination of the water tables due to septic tanks and the nearly non-existent sewer system…

What once seemed an idyllic island haven—the terrestrial outpost farthest away from any other inhabited area on the planet, the eternal point of reference in the imagination of those who long to escape the hustle and bustle of modern cities—is today in full-on environmental crisis.

What do we think poetry is? Just a random concoction of images, fleeting visions, beauty distilled to elicit various, “Ohs” and “Ahs”? There’s some truth to this; humans have yet to fully lose the capacity of wonder in the face of what is marvelous and at the same time ordinary.

Yet beware of thinking that poets ought not address what affects their immediate reality, whether attacks on the environment wherein they dwell or injustice against the dignity of their fellow humans. Since the days of the great Greek and Latin lyricists, sublime verse has taken up arms within ordinary reality, without devolving into propaganda.

This is how I read the first half of the poetry sequence Rights Taken, written by Víctor Ilich, presiding judge of the criminal court of San Vicente de Tagua Tagua. It is twelve terse, intense, revealing texts written with Rapa Nui in mind, the Easter Island of today that groans under the aforementioned problems.

I’ve never made a moai,

nor did my ancestors carve them.

From the quarry of my verses

I’ve only ripped out a THERE IS NONE.

There’s no more space,

it’s only 163 square kilometers.

There’s no more space,

not even enough for a forgotten pin.

There’s no more space in Hanga Roa

for the mercenaries of climate change.

There’s no more space, I tell you;

only the heart spreads out

when its root touches the edge of another soul.

Moais, de Ryan Fox

The Chilean judicial system has a mechanism of control over the legality of certain standards. The mechanism, the toma de razón (literally, “taking of reason or right”), is an obligatory review process that is the prerogative of the comptroller general. Here in these poems, the poet-judge becomes the comptroller of the needs of the islanders, heedless that some question his interest. Thus, in verse XI, he minces no words regarding his intentions:

And you, what do you know about Easter Island?

That it’s suffering, and that’s enough.

We must build a bridge

toward the soul’s needs.

I am acutely moved by the social conscience in these twelve verses of Víctor Ilich. I know they will profoundly touch the inhabitants of Rapa Nui, a land that boasts fine poets of its own, including another lawyer-poet, Mata-Uiroa Manuel Atan who, upon seeing the flag, proclaims: “Every day / I wake / you are my greeting // With my wind / you breathe / above my ground / you wave // Every day / I sit / I see you / you pierce my heart // Hotu’s descendants are happy / if they walk in Hangaroa / and you aren’t atop the poll // Listen, war banner / of foreign ancestors, / step aside / let me catch my breath…”

Now, on his island, that poet would know how to embrace Víctor Ilich, who wrote these Easter verses in the midst of the horrific wildfires that devastated continental Chile: “With embers on my head / and a raging fire in my bones / that, no matter how much I want to, I can’t stop.”

Poetry is a refuge for truth, truth being a rare commodity in our day.

Moai, del español Jorge Oliva López

III.

Poetry is also governed by love and knows how to feed legends. Akin to Neruda in The Separate Rose but with his own imprint, Roberto Contreras Olivares, minister of the Court of Appeals in San Miguel, wrote the second part of Rights Taken. He is a seasoned poet with several collections in print, just like his colleague Ilich. His offering leans toward genetic and mythical history. The springboard is the (imaginary?) dance he shared with the queen of Tapati, as if searching for the “mutual destiny” of their bloodlines.

Let us relish part of verse XII:

Tonight—I just know it—tonight

I’ll remember her name;

it’s been fastened inside me

since that other night

I took her hands

on the island

and we danced

with the waves

crashing into the cliffs,

the birds

cawing

and the ancient manutara

laying her single egg

carved with

ancestral signs.

This poetry sequence encourages solidarity among all Chileans without ever forgetting those who originally inhabited Easter Island. It follows in the footsteps of the renowned poet and Easter Island anthropologist Clemente Hereveri Teao, who passed away in 2007. In his poem “Sailing Ancestor,” he says, “Oh rain of the infinite / please fall / so our mouths don’t / dry out / with the ocean’s saltiness / while we sail / to the world’s navel / in the middle of the sea”.

And since Rights Taken is written with the inhabitants of Rapa Nui in mind, let us appreciate Hereveri’s text in its original tongue:

E te ua o te rani e

A hoa mai koe

O kava ro to matou haha

I nei, i te vaena o te moana

E hura nei

Ki te pito o te henua

I te vaena o te moana

Isla de Pascua, de Marcelo Bigliano

Out there in Chilean Polynesia, the verses of Contreras will be heard, we can only suppose, in the heights of the Ranu Raraku volcano; recited by, we can only suppose, a relative of Clemente:

Standing there

looking out from the island,

we are seeds

for other stars

of emerging constellations,

still lost

and blind.

Is this environmentalist poetry or earthly love poetry? It’s just poetry, plain and simple. That is what, in perfect lyrical union, Víctor Ilich and Roberto Contreras Olivares offer us.

This is how we go about constructing an irrefutable right to poetry.

This is how no one feels like a foreigner.

This is how song endures forever.

“Ena é, tangi nei.

Ena é. Tangi- tangi-nei

(This is the song…

This is the song that causes tears…)”.

April, in Tejares (2017)

Alfredo Pérez Alencart

University of Salamanca

El poeta Alfredo Pérez Alencart (Foto de José Amador Martín)

La traductora norteamericana Gretchen Abernathy

La traductora norteamericana Gretchen Abernathy

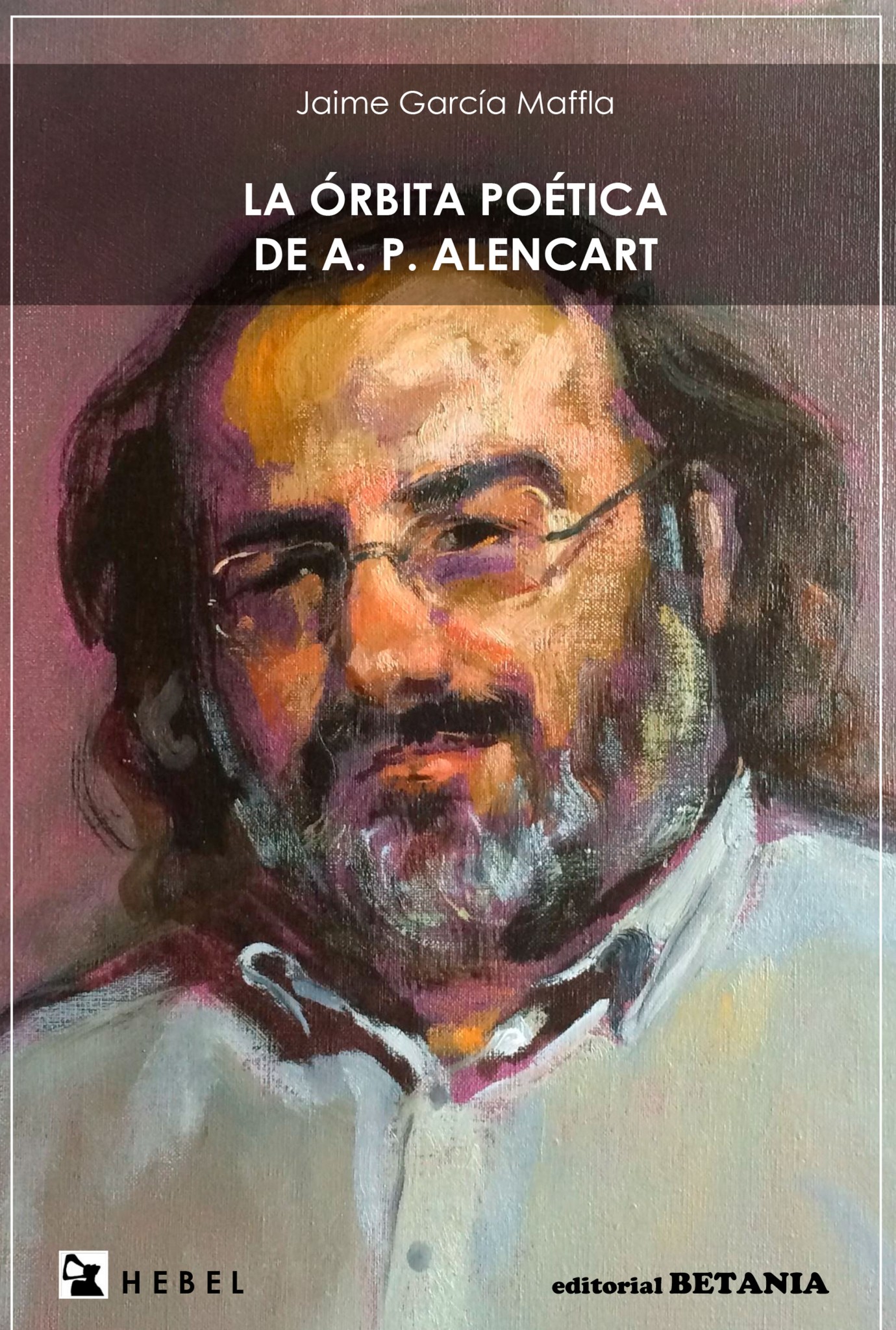

Alegato lírico por Rapa Nui, de A. P. Alencart

Deja un comentario

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.